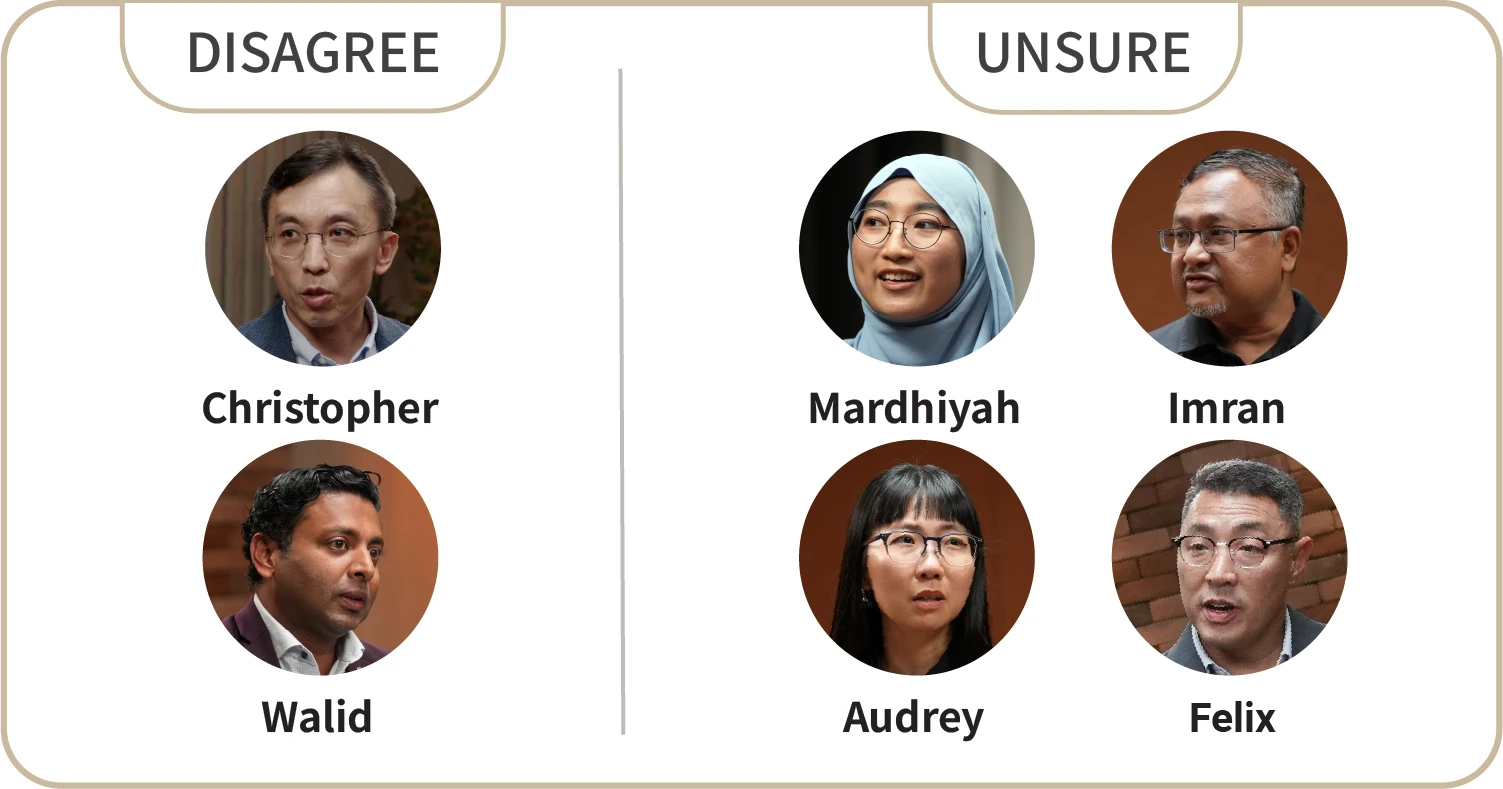

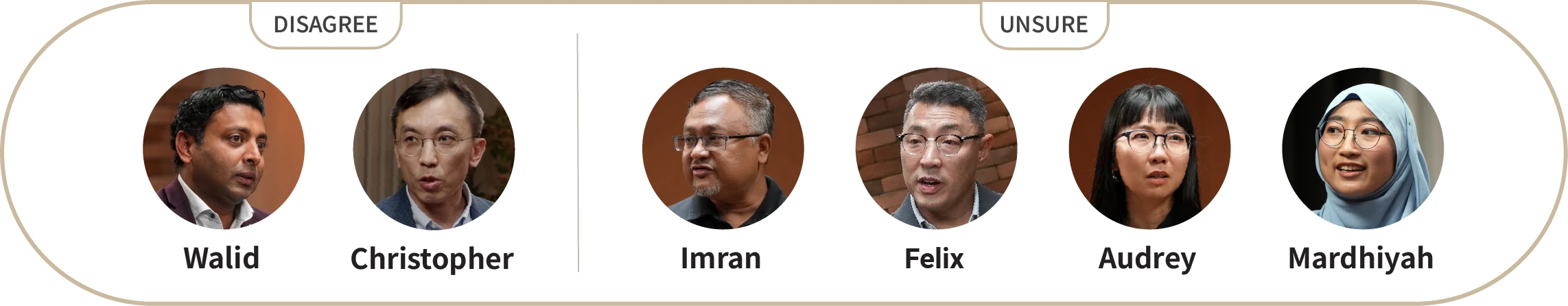

The roundtable dialogue kicked off with participants responding to statements presented from the moderator, on whether they “agree”, “disagree” or were “uncertain”.

Participants' Choices

While Singapore has made considerable strides in fostering harmony in its multiracial and multireligious society, conversations around global conflicts like the Gaza crisis still reveal the complexities of navigating deeply sensitive topics. Many Singaporeans might be comfortable with having everyday conversations with their friends from diverse backgrounds, but a seemingly invisible line still holds people back from discussing issues like Gaza.

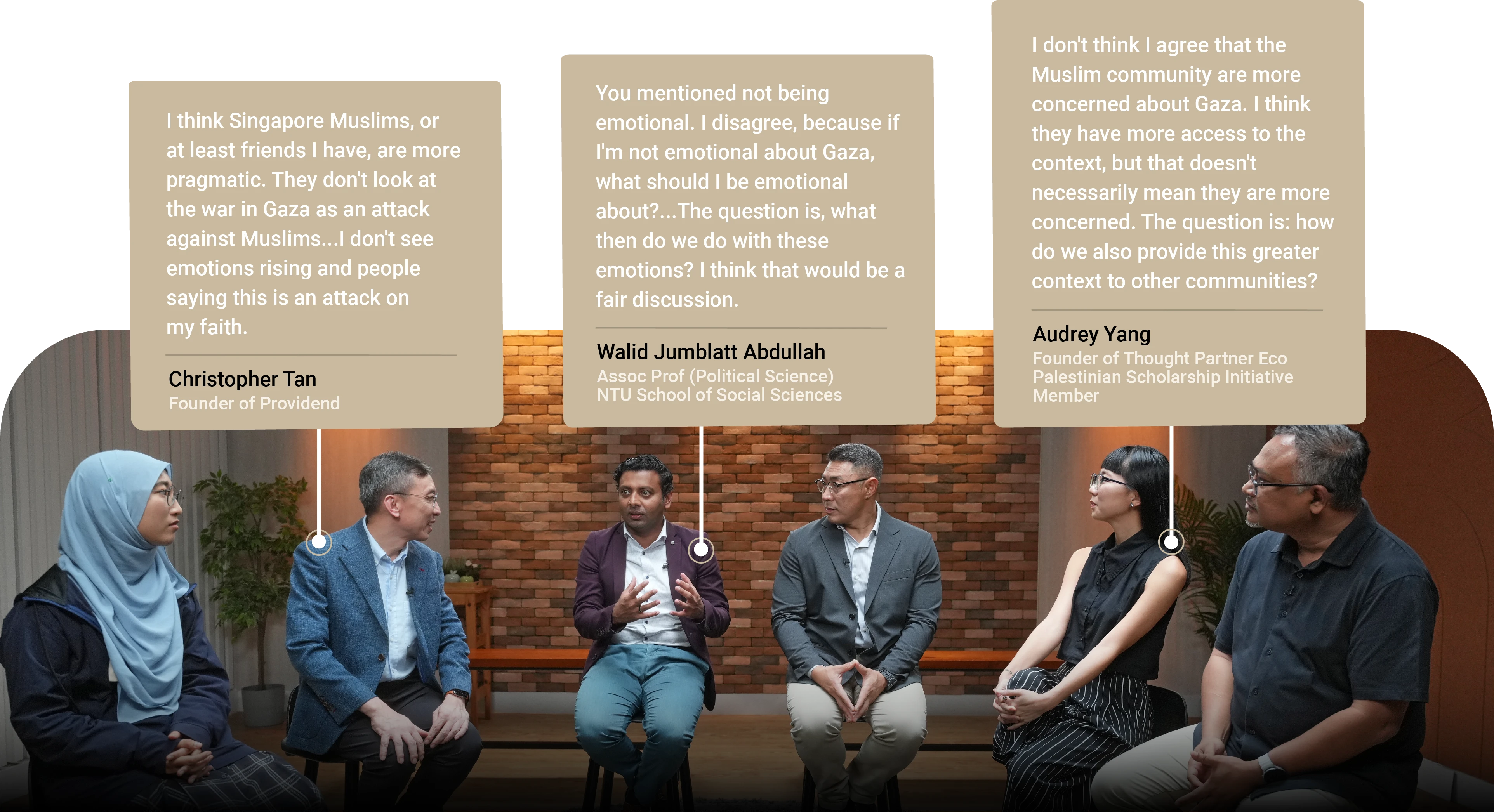

“I feel uncomfortable discussing the Gaza issue with friends of a different race or religion. Do you agree with this statement?” At a recent roundtable dialogue convened to discuss the Gaza situation and to forge inter-racial understanding, the six participating panellists – all from various backgrounds – were hesitant in tackling this straightforward question.

After some exchanged glances and nervous laughter, 20-year-old university student Nurainun Mardhiyah ventured to say she disagreed with the statement before changing her answer to “unsure”. Among the six participants at the dialogue, four chose to take this cautious position.

The uncertainty in the moment subtly reflects the unspoken boundary that still exists in conversations around challenging issues within a diverse and closely-knit society. People often don’t know how – or whether – to start such conversations, and some instinctively avoid them altogether.

It is evident, however, that the eruption of the Israel-Hamas conflict on 7 October 2023 has ignited active public discourse around the Gaza situation in Singapore. It also raises deeper questions: Should more be done by the government to provide public platforms for discussing Gaza? Is Singapore’s society mature enough to engage in constructive conversations on emotionally charged topics?

When an issue is so complex and multifaceted that many find it challenging to discuss even among their personal circles, it might be even harder for it to be broached on a more formal platform.

Although one would expect that the Gaza crisis – a prominent international issue – would be a regular topic of discussion in university classrooms, Mardhiyah, who is a second-year public policy and global affairs undergraduate at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), said that she usually only shares her thoughts about the topic in conversations with friends who share the same racial or religious background or similar views.

Lacking experience in discussing this topic with people from diverse backgrounds, Mardhiyah added that she has little understanding of how different backgrounds view the conflict and is unsure of how to strike the appropriate tone in such conversations. At times, she will carefully consider her words before sharing a social media post about Gaza.

I am not sure how to frame it in a way that doesn’t offend someone or make them feel like they are being lectured. It is important when talking about this issue that people are not scared to approach it, and that they don’t feel that it is impossible to engage when their views differ from mine.

Nurainun Mardhiyah

20NTU Student

Nurainun Mardhiyah

20NTU Student

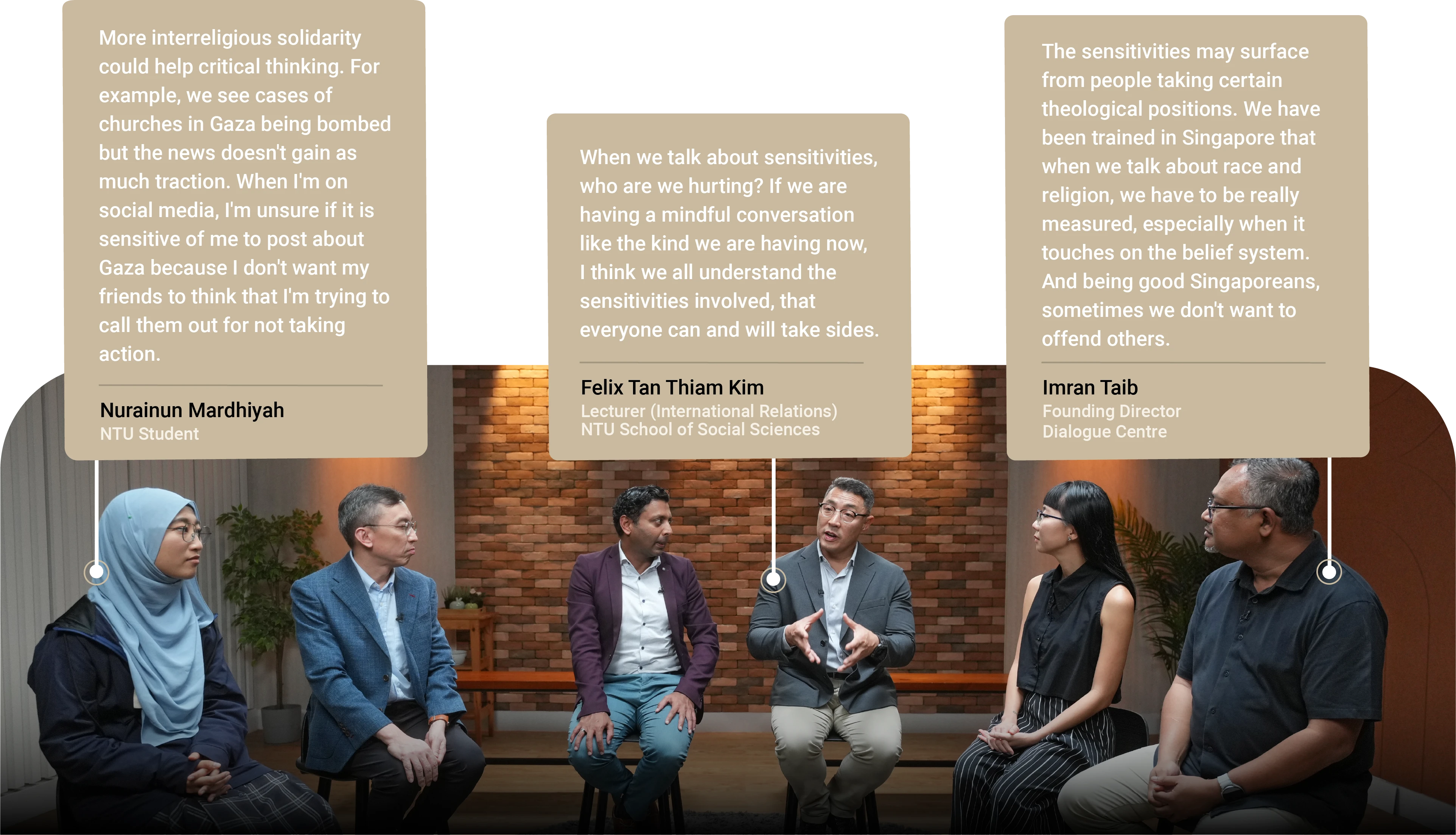

Fostering safe spaces for dialogue

At the roundtable dialogue, Dr Felix Tan, 52, a political observer and lecturer from the Public Policy and Global Affairs (PPGA) programme at NTU’s School of Social Sciences, agrees that creating safe spaces for people with differing views to comfortably engage in open and honest dialogue on sensitive issues is a tough but important task, especially in a diverse society like Singapore.

When discussing Gaza, people often end up labelling one another, he said. "Just because someone disagrees with one side, they get labelled as ‘anti-Semitic’ or a 'terrorist '. It is too binary."

Beyond polarising opinions, the Israel-Hamas conflict has proven to also carry the risk of inciting violent acts. According to data released by the Internal Security Department (ISD) in July, among the eight cases where Singaporeans found to be self-radicalised have been dealt with under the Internal Security Act, four were either triggered or accelerated by the ongoing conflict.

On the Gaza issue, the government has long sought to strike a careful balance between managing potential security risks and encouraging meaningful communication. Over the past two years, political leaders have largely engaged different community groups on the issue in closed door settings. In October 2023, in a joint statement, citing public safety concerns, the Singapore Police Force and National Parks Board declared that public events or assemblies related to the Israel-Hamas conflict would not be permitted.

Critics argue that the government’s approach curbed vital public discourse, but authorities maintained that such measures are essential to safeguard national security.

Diverging views within the Muslim community

For Imran Taib, 48, founding director of interfaith organisation Dialogue Centre, fostering dialogue across faiths is part of his daily work. From his observations, the Gaza issue not only risks dividing different communities, it also reveals internal differences within the Muslim community.

Sometimes I do meet Muslims who do not distinguish between Judaism as a religion and the political situation in Gaza or Israel. They tend to mix up the two. But when you try to tell them: look, these are distinct, you may get accused of being pro-Zionist. That makes conversations difficult.

Imran Taib

48Founding Director

Dialogue Centre

Imran Taib

48Founding Director, Dialogue Centre

Imran also cautioned that in an information-saturated online world, the flood of emotional discourse and opinions can influence public sentiments, but these views may not always consider Singapore’s unique context.

But all six dialogue participants were unanimous in agreeing that deepening public understanding of complex issues like Gaza is important for strengthening social cohesion, even if the conversations can be challenging.

Imran stressed that the more difficult the topic, the more important it is to find ways to talk about it – and to equip people with the skills to have meaningful civic conversations.

"We are already a very diverse society – not just in terms of religion, culture or ethnicity but also in that people have very different opinions. It is time we acknowledge that and learn how to develop the muscles to deal with our differences, rather than sweep it under the carpet," he said.

Speaking at the roundtable dialogue, Dr Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, 40, associate professor in politics at NTU and an active voice on Palestinian-related issues in Singapore, acknowledged that he might be in a "bubble" or social comfort zone when he writes and speaks about Palestine, as the people who actively engages with him are often those who agree with him. At the same time, he said that it is important to be conscious of this and to expand one’s social circles as much as possible to engage with people who hold different views.

"The only way forward is to have more discussions, because whether we like [their views] or not, we share the space with other people."

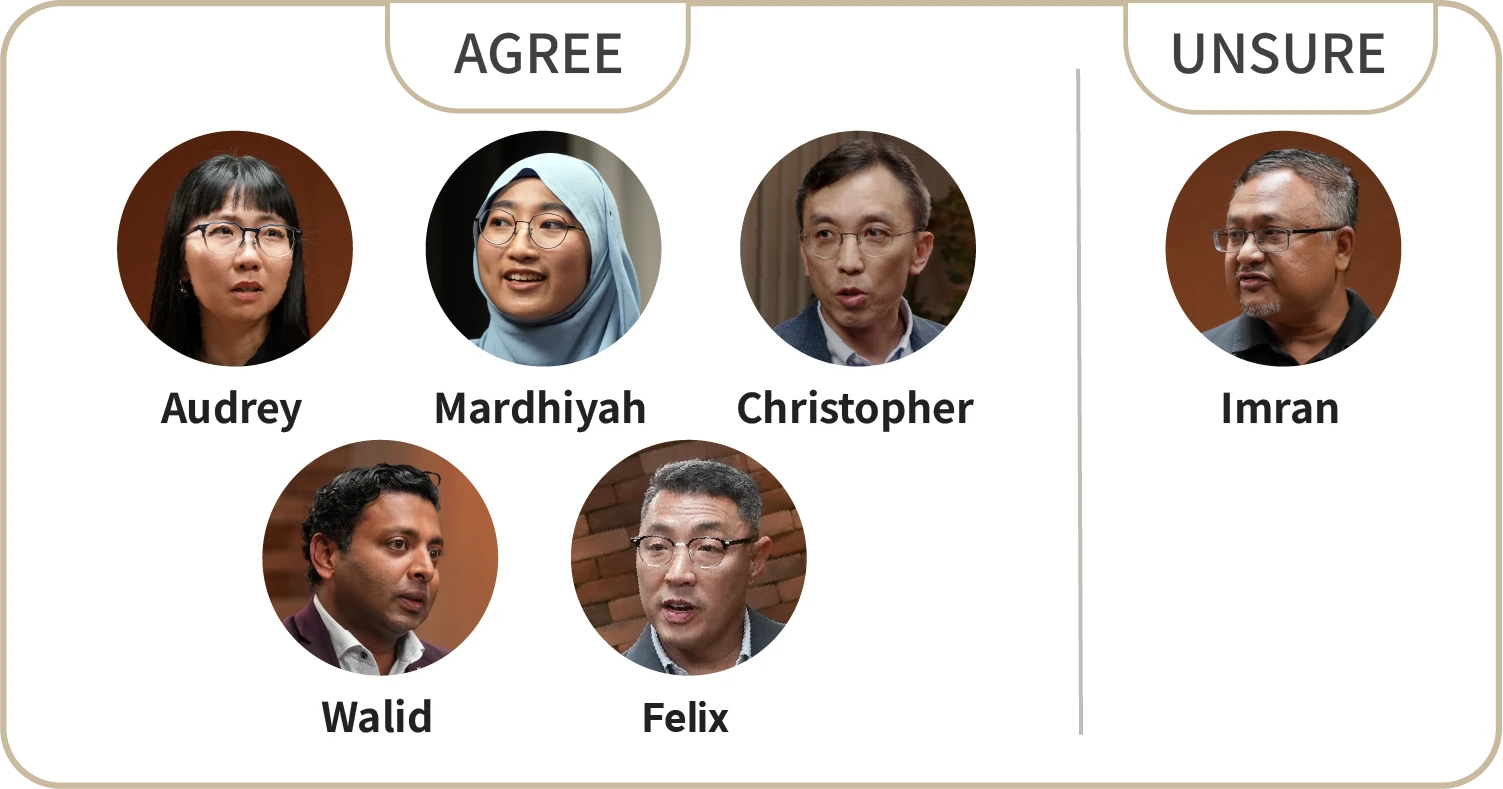

Participants' Choices

"The situation in Gaza is not a small family quarrel, it is an active genocide."

This has always been how Audrey Yang, 36, characterises the Gaza crisis – it is her fierce lament for a people under siege, with their lives shattered beyond recognition.

Yang, a sustainability consultant, is also a member of the grassroots project Palestinian Scholarship Initiative, launched in October last year. As of July 2025, the project has raised more than S$510,000 to support four young Palestinians to pursue higher education in Singapore’s universities this year.

According to the latest reports, 90% of homes in Gaza have been destroyed or damaged in the conflict. Schools, hospitals and places of worship have not been spared.

An estimated 1.9 million people – around 90% of Gaza’s population – have been forcibly displaced, while the civilian death toll has surpassed 60,000, with one in three victims being children.

Healthcare services have collapsed under overwhelming strain and humanitarian relief efforts have faced systematic obstruction.

As Yang’s remarks highlighted, the scale of devastation in Gaza is both staggering and heartbreaking. From a humanitarian standpoint, many believe that Singaporeans from all walks of life, no matter one’s race or religious background, should be concerned about the ongoing tragedy that has befallen the people of Gaza.

At the roundtable dialogue, when the participants were asked to express their opinion on this, the majority were in agreement that the Gaza crisis warrants our attention and is a matter of universal concern.

When understanding falls short

Yet not all communities are equally engaged and the level of concern could vary because of personal factors, whether it is religion, values or individual understanding of the issue.

One respondent who chose a different answer from the rest was Dialogue Centre’s Imran, who said he was uncertain if the situation in Gaza is a major concern for all Singaporeans.

“I am not sure because we don’t have data on whether it actually is a major concern for all. What we have are anecdotal opinions,” he said.

Adding that he personally feels strongly about the issue, he noted that the depth and breadth of discussions on the Gaza conflict can vary widely from person to person. Setting aside race and religion, one’s social circles – who one talks to and interacts with – might also determine their level of engagement with the Gaza issue.

Yang agrees, noting that most people remain focused on bread and butter issues and their daily needs. In Singapore, even when it comes to domestic issues, some only have a surface-level understanding; the Gaza conflict is seen as faraway and might be even harder to grasp, said Yang. In the early days of the conflict, some hadn’t even heard of Palestine, nor know where Palestine is, she added.

All six participants agreed that they did not see Gaza as just a religious issue – it is much more complex and multi-dimensional. It stands as the world’s greatest humanitarian crisis today, and challenges the international legal order, with wide-ranging implications for regional stability and global security.

Another participant, Christopher Tan, 55, founder and CEO of Providend, an investment management and wealth management firm, pointed to the early days of the conflict when international oil prices fluctuated wildly as a clear sign that the impact of the Gaza crisis is far from confined to the region.

If we don’t have a proper conversation [about the Gaza issue], it is going to tear the fabric of society…It is not just a local problem, it has got ripple effects. If the conflict prolongs, there could be a wider outbreak of war in the Middle East and other countries may get involved.

Christopher Tan

55Founder of Providend

Christopher Tan

55Founder of Providend

All the participants agreed that dialogue is both essential and difficult. Any honest conversation would involve taking positions and in a diverse society, being able to hold open, respectful discussions despite having deeply differing views remains a real challenge.

For example, in May this year, concerns arose over foreigners trying to influence Singapore’s general elections by swaying the local Malay-Muslim community’s stance on Palestine and the outcome of the vote. The government stepped in with warnings and interventions in a bid to prevent both foreign actors and local provocateurs from weaponising identity politics, misleading voters and threatening social stability.

Respecting local realities while feeling deeply for Gaza

With their shared religious identity with the Palestinian people, Singapore’s Malay/Muslim community naturally feel a stronger emotional connection to or “affinity” with Gaza, said Dr Walid. However, he also pointed out that the community’s deep feelings about Gaza long predates the current Israel-Hamas conflict and emphasised that having these strong emotional responses to the seemingly unending crisis in Gaza is not the issue.

What matters is how these feelings are channelled into meaningful actions that align with Singapore’s national context and realities, he suggested. In fact, the emotional resonance triggered by the crisis now extends well beyond the Muslim community, said Dr. Walid, who observes that the complex humanitarian, legal and moral aspects of the Gaza conflict have sparked broad empathy and has resonated especially among the young.

Yang offered a slightly different perspective. She cautioned against assuming that religious commonality necessarily leads to stronger empathy for the Gaza crisis. Instead, she believes that how the issue is framed or media narratives play a more direct role in shaping public concern.

As such, she stressed the need for news outlets to exercise care and responsibility in their coverage and choice of words. A society that can engage in conversations where passion does not override reason will reflect true maturity and its commitment to diversity while building common ground.

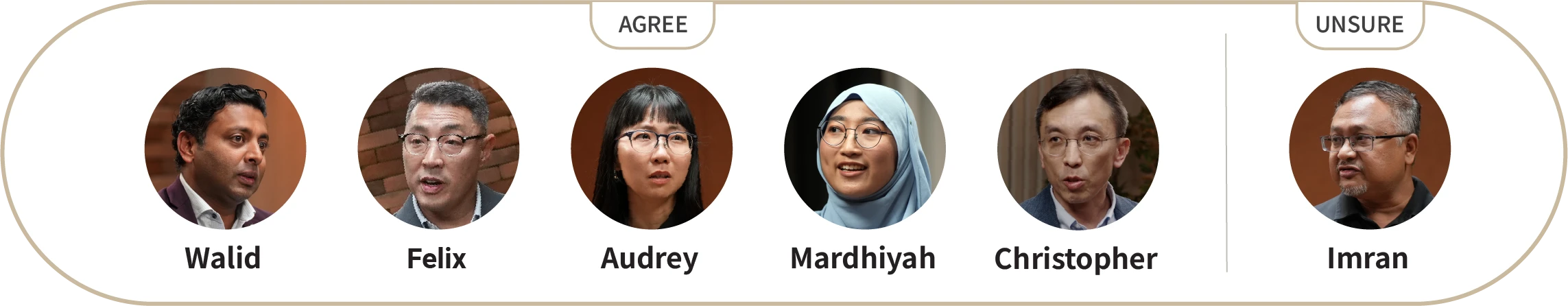

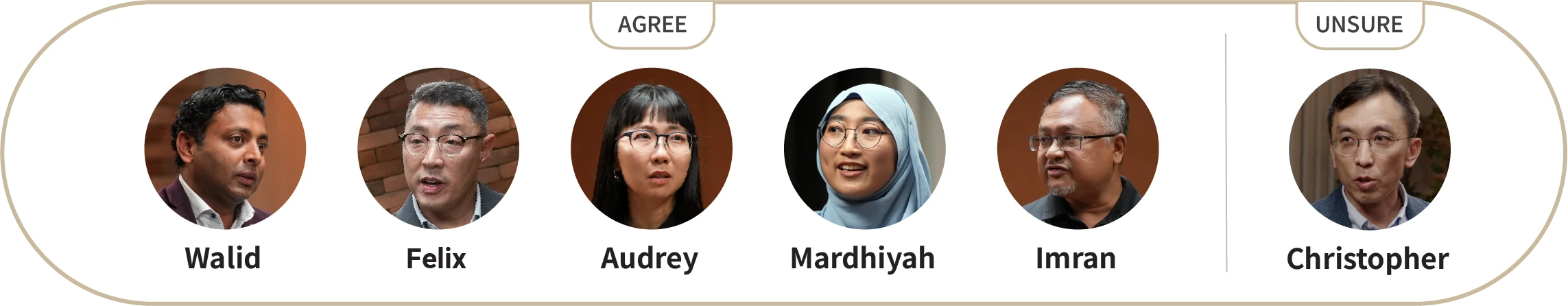

Participants' Choices

The statement “Singapore should do more for Palestine” may seem straightforward, but it sparked deep reflection among the six participants at the roundtable dialogue, prompting them to ask: What has Singapore done? What has it not done? What more can be done? And is it even possible to do more?

The Singapore government's humanitarian assistance to Palestine has been widely recognised. Yet, for some citizens watching the crisis in Gaza unfold from afar, there remains a sense of helplessness.

The feeling could reflect a deeper desire, that beyond offering aid and donations, Singaporeans hope for more open and safe spaces to express their concern and deepen their understanding and conversations on the Gaza crisis, all while respecting Singapore’s multiracial and multireligious sensitivities.

Among the six participants, five agreed that Singapore should be doing more to express solidarity with Palestine, while one remained unsure, although their views were similarly aligned. All expressed an understanding of Singapore’s position and limitations as a small state.

Imran, who supports doing more, noted that Singapore has already delivered nine tranches of humanitarian aid totalling over S$20 million to Palestine, while also offering to train civilian officers, to help prepare the Palestinian people for eventual statehood. He acknowledged that he was, hence, uncertain about what else Singapore can realistically contribute.

The government recently announced a 10th aid package, bringing the total aid amount to over S$24 million.

Tan, Providend’s CEO, the one participant who expressly said he was unsure what more Singapore could do, pointed out that Singapore had received significant military support from Israel in its early years of nation-building, and that the bilateral relationship has long been strong.

Given that, the government’s public criticism of Israel’s actions in Gaza as a violation of international humanitarian law is both courageous and surprising, he said.

As for what more Singapore can do for Gaza, Tan reckoned it is easier said than done, given the limitations of a small state.

An appeal for greater space

But is Singapore’s ability to do more limited by the realities of being a small nation? "We shouldn’t keep using this argument" was the swift retort by Yang from the Palestinian Scholarship Initiative.

She argued that whether more can be done depends more on "whether the government allows it". "Now the safe ways to participate are through monetary donations and charity work. But what is beyond that? The government should create a safe space and environment so that people know they can do more – in a non-aggressive way – and it will be allowed, without fear of being penalised," said Yang.

Her view was met with agreement from other dialogue participants. Some suggested that the government could go beyond material aid and consider allowing other intangible forms of support such as allowing peaceful public expressions of solidarity, enabling more civil society-led dialogue.

Other recommendations include improving public awareness of Gaza's history and its ongoing challenge, as well as reconsidering the display of Israeli-made weapons at Singapore airshows.

Should Singapore recognise Palestine?

The question of whether to recognise the Palestinian state has recently come under the spotlight, with an increasing number of countries taking the step as a way to condemn Israel's military actions in Gaza. Most of the participants at the roundtable dialogue voiced their collective support for Singapore to formally recognise Palestine.

NTU’s Dr Tan put it plainly: " I think there was an issue that we should not be recognising Palestine because we will cause more problems for Palestinians. The questions that come to mind then are, aren’t the Palestinians already suffering without the recognition? Will recognition affect anything? Will it bring more suffering?"

On September 22, two weeks after Lianhe Zaobao and Berita Harian organised the roundtable dialogue, the government announced that Singapore will recognise Palestine when it has an effective government that accepts Israel’s right to exist and categorically renounces terrorism.

Singapore also announced the imposition of targeted sanctions – for the first time – on the leaders of radical right-wing settler groups or organisations that have been responsible for acts of violence against Palestinians in the West Bank.

Imran pointed to how the indiscriminate killing of civilians, including vulnerable women and children, in Gaza should be seen as a "moral question", and expressed frustration over how Singapore’s major religious organisations have not come together to issue a joint public statement condemning the violence in Gaza, as he said they often do, in the form of inter-religious solidarity in response to acts of terrorism or extremism.

Dr Walid said he shares the same sense of dismay as a Muslim. He noted that in Singapore’s multiracial context, the burden of upholding racial and religious harmony often falls disproportionately on the Muslim community.

Following the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas conflict, Singapore’s top Muslim cleric had extended condolence to the Chief Rabbi in a formal letter; yet, when Israel launched military attacks on Gaza, there was no reciprocal gesture of concern toward the Muslim community, said Dr Walid.

We [referring to Muslims] are used to it, that when there is an act of terrorism – even if it happened far away, the community will be very quick to condemn it, to distance ourselves and say that Islam does not stand for this. That has almost been our ‘autopilot response’ whenever something happens. Sometimes I feel that that is not reciprocated.

Walid Jumblatt Abdullah

55Assoc Prof, NTU School of Social Sciences

Walid Jumblatt Abdullah

40NTU School of Social Sciences

Assoc Prof (Political Science)

Wong Siew Fong

Associate News Editor

Lianhe Zaobao

A difficult yet necessary dialogue

Securing speakers for our roundtable dialogue on the Gaza issue—as part of the multimedia special report—turned out to be the hardest challenge of our project. Nearly half of those we approached declined the invitation.

A common refrain among invitees to the dialogue is, “Why hold such an open dialogue on such a sensitive topic?”

Everyone we approached, however, is deeply concerned about the Gaza issue and agreed that a broader discussion in Singapore is needed, but did not want to speak about it on a public platform.

Their hesitation underscores the significant challenges of addressing sensitive topics within our multi-racial and multi-religious society. This raises important questions: Is there a safe space for these conversations—one that feels unconstrained and minimises the risk of misinterpretation to talk about Gaza? Why are such conversations even necessary in Singapore? These were the questions that weighed on many invitees, and they were the very same ones our production teams meticulously considered at every step - from the initial ideation to execution, to final production.

This dialogue was not merely about the situation in Gaza; it served as a microcosm of our diverse society. Beyond creating a platform for different voices to be heard across racial and religious backgrounds, the production team sought to delve into a more profound issue: In a relatively mature and diverse society like ours, why do some sensitive topics remain so challenging to discuss? If we shy away from such conversations, can we truly grasp each other’s perspectives and concerns?

After considerable effort from the team, a diverse group of six individuals and academics accepted the invitation to the studio. For most, it was their first meeting, and the atmosphere was initially somewhat stiff as they began their on-camera discussion about Gaza.

When asked whether Muslims were more concerned about the issue, one participant, Christopher Tan, articulated his perspective slowly and with great care, seemingly to avoid any misstep. Midway through his response, Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, seated beside him, furrowed his brow, hands resting tensely on his thighs as he gathered his thoughts. Eventually, he interjected, seeking clarification and offering a differing viewpoint.

This initial moment of disagreement proved to be a turning point in the dialogue. Though the air grew slightly tense for a moment, the frank exchange between the two participants broke the ice, easing tension and allowing open dialogue. Participants gradually relaxed, engaging naturally without much guidance from the moderators, asking and responding to each other. When a point resonated, some even instinctively patted each other’s arms, like old friends.

The conversation served as a powerful reminder: often, the most uncomfortable conversations are essential for fostering trust and friendship. A harmonious multi-racial and multi-religious society must not only seek common ground, but also actively listen to and acknowledge differences. Engaging in open and candid dialogue is the first step. Only by truly understanding and respecting each other’s perspectives can we build a more resilient, cohesive, and vibrant society.

Siti Aisyah Nordin

Social Media Team Lead

Berita Harian

What Gaza teaches us about difficult conversation

It is undeniable that the plight of Palestinians resonates deeply with the Malay/Muslim community.

It is an issue that has been raised in Parliament by our Acting Minister for Muslim Affairs, and echoed in Friday sermons across our mosques.

For most Malay/Muslims, Palestine is not distant or abstract; it is a conflict that hits close to the heart.

Even so, in a multiracial, multireligious society like Singapore, such concerns should never be confined to one community alone, as that would only narrow the conversation.

Discussions on topics as sensitive as Gaza are never easy or comfortable - and even getting non Malay/Muslim participants was a challenge - but that is precisely the point.

When Berita Harian and Lianhe Zaobao brought together Singaporeans of different races, faiths and professions in a dialogue to talk about Gaza, the goal was never to produce a consensus.

Nor was it to make every participant walk away holding the issue as close to their heart as the Malay/Muslim community does.

The purpose was to test whether we could confront such a fraught topic - sit together, hear each other out - without retreating into silence or hiding behind safe statements.

Listening to the exchange, it became clear that the value of the dialogue was not in polite agreement, but in moments of tension.

It allows us to ask hard questions, make uncomfortable statements, and admit what we do not know without fear.

Through it all, one thread ran consistently across the dialogue: compassion and empathy. This thread matters if we are to keep these conversations going.

When sensitive issues are swept aside in the name of ‘not rocking the boat’, we might mistake silence for ‘harmony’, avoidance for ‘cohesion’.

Avoiding difficult conversations - whether on Gaza, race or inequality - does not preserve unity but only leaves the loudest, most divisive voices to dominate unchallenged, especially online, without the balance of dialogue.

The dialogue showed that these conversations are possible, but it also exposed our gaps.

Many admitted that they lacked the historical grounding to go deeper in the conversations. Others worried about offending friends of another race or faith by “posting about Palestine on social media.”

These might be ‘warning signs’ that should not be ignored, as a society that avoids hard issues may one day find itself unable to talk about them at all.

Social cohesion is not the absence of difference, but the ability to manage the differences with dignity and respect.

Disagreements surfaced, but honesty and openness allowed participants to connect more deeply.

That, again, was precisely the point.

Full Video

Video Highlights

-

00:00 - 01:53

Six Singaporeans join in an open dialogue on the Gaza issue, presenting diverse perspectives.

-

01:53 - 14:09

The situation in Gaza is a major concern for Singaporeans, regardless of race and religion.

-

14:09 - 27:44

Singapore should do more for Palestine.

-

27:44 - 41:00

I feel uncomfortable discussing the Gaza issue with friends of a different race or religion.

-

41:00 - 48:53

Understanding difficult issues like Gaza can strengthen our social cohesion.